1.9 Reading between the line

Study Notes:

Macroeconomics concepts, such as real GDP, inflation, the unemployment rate, the fiscal deficit, and the interest rate, make headlines on a daily basis. Finance segments on national news broadcasts discuss complex macroeconomic issues that are not well understood by the public. Consequently, from the outset the public discourse contains significant errors that render it almost impossible for participants to make informed assessments of macroeconomic developments independently of the associated politics. Social media exacerbates this problem. Appeals to ‘common sense’ and intuition have all become dangerous norms in these forums. Our propensity to generalise from personal experience, as if that experience equates to general knowledge, continually leads these ‘Facebook’ macroeconomics debates into combative dead ends of false reasoning from false propositions.

The fact that mainstream macroeconomics has retained its hegemonic status in the face of its failure to resonate with reality is due in no small measure to the way economics debates are framed in the public discourse. Framing refers to the way an argument is conceptualised and communicated by speakers and listeners. Conceptual models and representations are used in this process. Research in cognitive philosophy and cognitive linguistics suggests that the models that constrain our thinking operate at a largely unconscious level, and that the abstract concepts we draw on are mostly of a metaphorical nature.

We can summarise what this means in the following way. Embodiment relates to everyday activities such as grasping something with our hands, or, standing and walking. We relate these physical actions via the use of metaphors to try to understand the world around us. For example, we understand concepts associated with ‘more’ or ‘less’ in terms of a direction ‘up’ or ‘down’ as a consequence of our physical experience of interacting with our environment. Metaphors concerned with direction are also employed in our reasoning about being happy or sad (as in ‘that was an uplifting film’ or ‘I’m feeling down’) and success or failure (as in ‘they are climbing the corporate ladder’ or ‘they have fallen from grace’). We think about quantity in terms of direction such that ‘more’ is conceptualised as an upward trend, and ‘less’ is figured as downwards. In relation to our general thinking about money, ‘more’ is typically good and ‘less’ is typically bad. The idea that a bigger fiscal deficit can be a desirable thing is thus counterintuitive in a very basic sense. A deficit is conceived as a shortfall, a bad.

Proponents of mainstream macroeconomics have been extremely successful in their use of common metaphors to advance their ideological interests. Ideologically loaded myths are accepted unchallenged by the public as truths.

Recent psychological studies have highlighted the extent to which pre-existing biases influence the way in which we interpret factual information, including straightforward statistical data. This presents a further problem for the communication of research findings that may be counterintuitive or controversial, or that challenge the dominant discourse about public policy design, as in the case of economic austerity or climate change.

Further, it is often the case that the language that is used to advocate a progressive alternative actually serves to reinforce conservative myths. It has been suggested that language is so important in learning that there is a need to develop new terms that are not associated with orthodox economics in order to communicate a new progressive macroeconomics, such as MMT. But there is a tension between any benefits that may accrue from the development of such a new language, and the necessity to couch the argument in terminology that the public are familiar with when discussing economic outcomes.

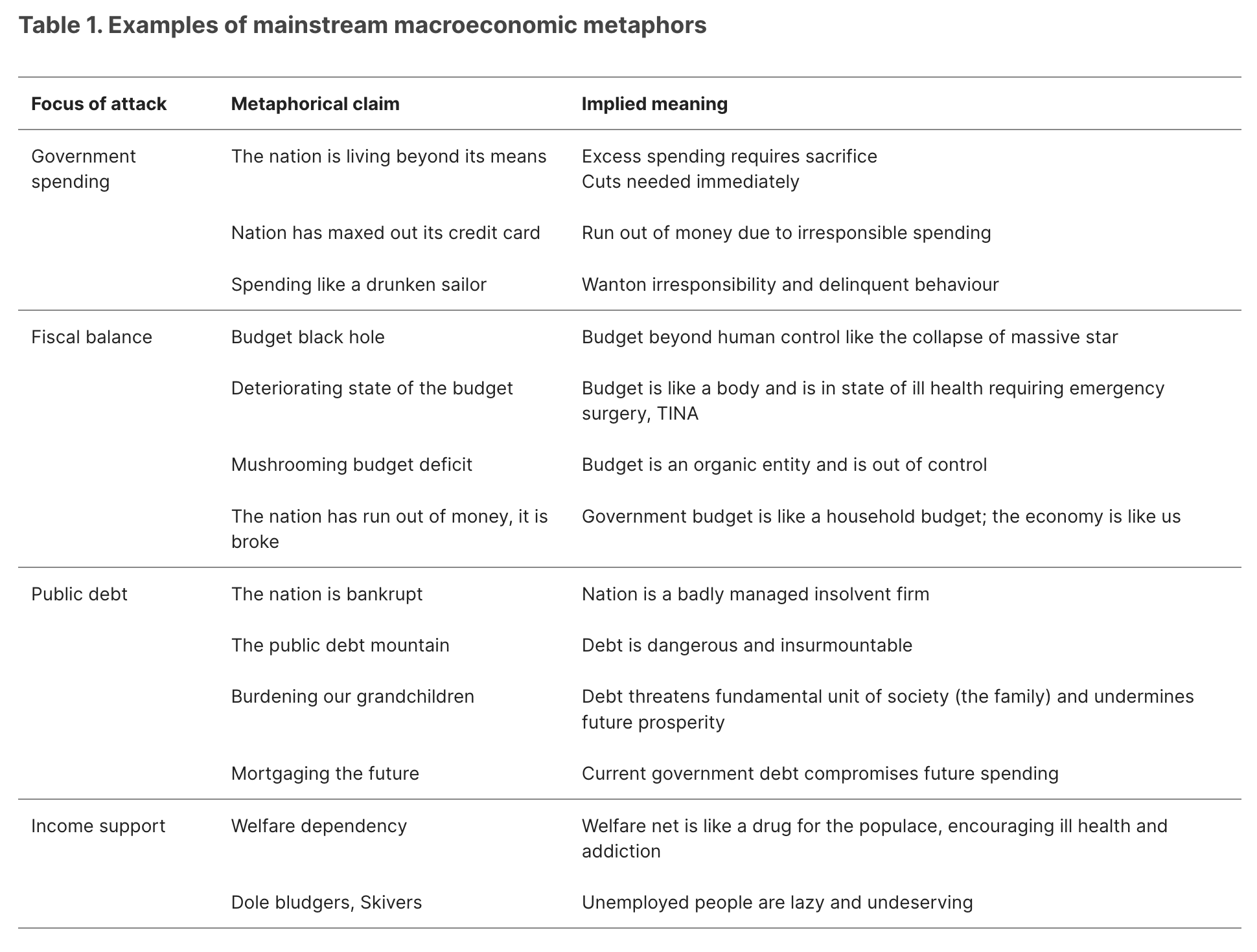

Table 1 shows some of the popular examples of metaphors used by mainstream economists and commentators to focus their attack on government spending, deficits, public debt and income support payments for the most disadvantaged workers.

In Table 2 we present a summary of the MMT alternatives to the framing. Comparison of the two tables demonstrates how different the two approaches are.

If you have library access to the Journal of Post Keynesian Economics then you can read a more detailed discussion of these issues in the article: Louisa Connors and William Mitchell 'Framing Modern Monetary Theory' (Volume 40, No 2, 2017). If you cannot access that article then you can read the Working Paper version that is freely available here.